Donald Trump Is A Traitor

Today is January 6th, 2026. Five years ago today, the Congress met, as prescribed by law, to count the electoral votes from the 2020 presidential election and certify the winner thereof. This had happened every fourth January 6th since the adoption of the Twentieth Amendment, almost always without any kind of fanfare. But this time was different, and it was different because of Donald Trump.

Determined to stay in power despite having lost the election to Joe Biden, Trump – in Liz Cheney's famous formulation – summoned a mob. He told his followers to assemble in Washington on the 6th, he made a big speech about how the election was being stolen. He said that they would be "marching over to the Capitol building to peacefully and patriotically make your voices heard." But of course, when the mob reached the Capitol, they were not peaceful and they were not patriotic. They literally stormed the building, overwhelming the defenders, literally running barricades. They entered the Capitol building itself, something the Confederacy had never managed to do. They forced the Congress to disrupt its session, and literally flee for their lives. By some miracle, the mob did not find any Congressfolk to kill. They were not coy in their intentions, if they had found any. Or if they had found Mike Pence, whom they were calling to have hanged.

Five days later, the House of Representatives impeached Trump for this. For, specifically, "incitement of insurrection." He was ultimately acquitted in the Senate, though a majority of Senators voted to convict; many of those who voted to acquit did so on the ostensible (and very wrong) theory that, as Trump was no longer in office, the Senate no longer had jurisdiction over him. Meanwhile, many members of the mob itself were charged with crimes including seditious conspiracy. Trump himself was ultimately indicted for a number of crimes, conspicuously not including seditious conspiracy. These charges were never tried, thanks to the Supreme Court's extremely bad ruling in Trump v. United States (2024) and then Trump's victory in the 2024 election. There has been debate about whether January 6th constituted "rebellion or insurrection" within the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment's third section, which would disqualify Trump from future office-holding. (It was, and it does.)

But in all of this, in all the grand public discourse over Trump's culpability for what happened five years ago today, there's one word I haven't really heard used: treason.

There's reason for this. Our legal culture is extremely cautious about calling people traitors. The Constitution provides a specific, narrow definition of treason, not least because the capacious definition under English law had been a powerful tool of abuse and oppression. I myself spent much of Trump's first term in office saying that his involvement with Russia, for example, was not actually treason, even though it seemed to have that of betrayal about it. But despite all that, I do believe that Donald Trump committed treason – literal, formal, legal treason – five years ago today. I thought so on the day itself, and I still think so on reflection. To my knowledge, no one has ever written at any length about the reasoning behind this view, so here goes.

We begin, of course, per the old cliché, with the text of the Constitution. The Treason Clause is the first clause of Article III, Section 3. It reads:

Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying War against them, or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort.

The relevant federal criminal law copies this language exactly, and is understood to run to the full extent of what the Treason Clause allows.

Now the important thing to understand is that almost every allegation of treason there's ever been has concerned the second prong of this definition. When you think of, like, a spy defecting to the Soviet Union, that's "aid and comfort" treason.

Except, it wasn't. There's a key limit in the definition of "aid and comfort" treason, and it's not very well understood by laypeople: the word "Enemies." This is a term of art. It has a very specific legal meaning in the context of the Treason Clause: it means a country with which the United States is formally at war. Emphasis on "formally": to a first approximation, the diplomatic/legal state of enmity requires a declaration of war. And we haven't declared war on anyone since World War Two. We've fought a lot of wars in that time; Congress has even authorized a lot of wars in that time. But an Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF), while it does, y'know, authorize the use of military force, does not create a formal state of war.

And if that formal diplomatic condition does not exist, then it is impossible for anyone to commit "aid and comfort" treason. This is why no one has been charged with actual, factual treason since the Second World War. It's literally impossible. People who defected to the Soviet Union were charged with one of the lesser, treason-like offenses under U.S. law, typically violation of the Espionage Act. This is what, for example, the Rosenbergs were prosecuted, and ultimately executed, for.

And so when Trump himself exhibited disloyalty in favor of Putin's Russia around the 2016 election, I, and others who knew the law, were saying, no, this isn't treason. It literally cannot be treason, because we are not at war with Russia. Notwithstanding that Russia is considered a geopolitical adversary, the formal state of enmity does not exist. It's not treason. Likewise, the activities that led to Trump's first impeachment (i.e. his attempted extortion of the president of Ukraine, a guy named Volodymyr Zelenskyy, I wonder what ever happened to that guy??) was not treason. Nothing is ever treason. Nothing can be treason.

Except...

Except that all this time, I have only been talking of one-half of the Treason Clause. There is an entire other way you can commit treason under the Constitution: by "levying war" against the United States.

Nothing I've just been saying about the limitation of "aid and comfort" treason applies to "levying war" treason. It does not require an "Enemy," and therefore does not require a declared war. It just requires an act of war on the part of the traitor.

Like sacking the Capitol, perhaps.

It was plain enough to me, on the day itself, that Donald Trump was making war against the United States, and therefore was a traitor. But my intuition is not itself the law. Can we say more about what constitutes "levying war" within the meaning of the Treason Clause?

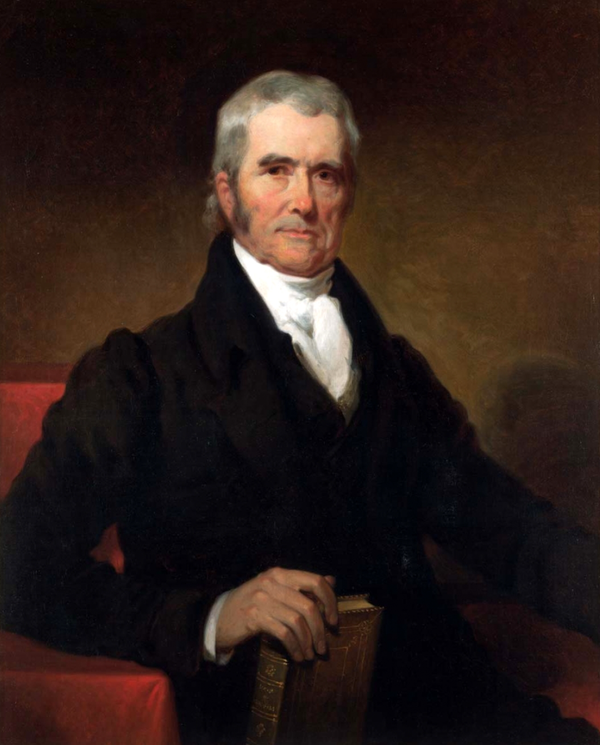

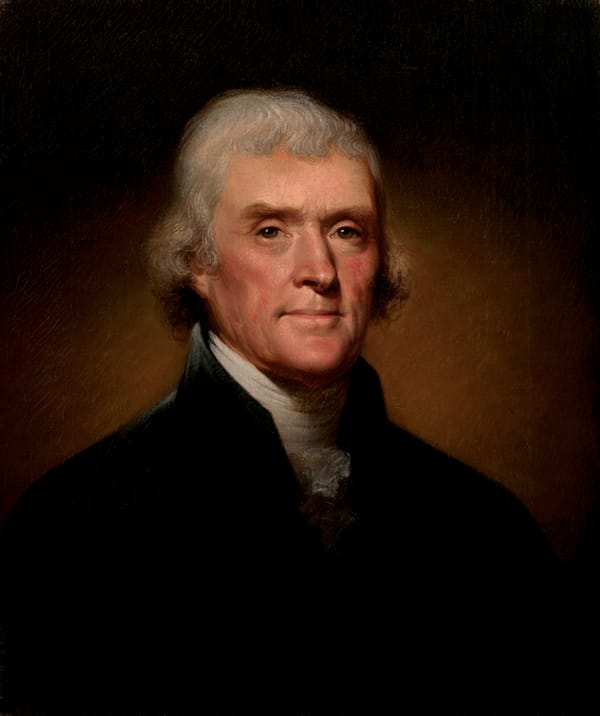

There is not a lot of precedent about this kind of treason, because it hasn't happened very much. The unpleasantness of 1861-65 certainly qualified. But there just aren't a lot of examples of Americans trying to make war against America. That's the thing about being the Leviathan: it's an obviously terrible idea to pick a fight with you. Aaron Burr raised an army in Texas in 1805-07, and was charged with treason for it, but ultimately let off by the Supreme Court because it wasn't clear who exactly he meant to use that army against. There's really not a lot.

But there is one illuminating source for what the Founders might have meant by this language: Blackstone's Commentaries. For those who don't know, William Blackstone was the leading English jurist of the eighteenth century. His treatise, Commentaries on the Laws of England, written in the 1760s, was the leading authority on, well, the laws of England. Certainly the American Founders regarded it that way.

Chapter Six of Book Four of Blackstone's Commentaries discusses treason, "high treason" specifically (this meaning treason against the King; "petty treason" was a separate thing). Very much in sympathy with the Treason Clause in our Constitution, Blackstone says that it is essential for treason to be precisely defined, and he criticizes English law for allowing the judges too much latitude to find anything they wanted to be treasonous. But, he wrote, overall the law seemed to identify seven "species" of high treason. Five of these are specifically excluded by our Treason Clause: imagining the death of the king, violating (sexually) the king's wife or eldest daughter, counterfeiting the great seal of the realm, counterfeiting the king's money, and killing the chancellor, treasurer, or one of the king's justices.

The other two species of treason Blackstone identifies are exactly the two retained by our Constitution: levying war against the king in his realm, and adhering to the king's enemies, giving them aid and comfort. It is the former that concerns us here, so let's look at everything Blackstone has to say on the subject:

THE third species of treason is, “if a man do levy war “against our lord the king in his realm.” And this may be done by taking arms, not only to dethrone the king, but under pretence to reform religion, or the laws or to remove evil counsellors, or other grievances whether real or pretended. For the law does not, neither can it, permit any private man, or set of men, to interfere forcibly in matters of such high importance; especially as it has established a sufficient power, for these purposes, in the high court of parliament: neither does the constitution justify any private or particular resistance for private or particular grievances; though in cases of national oppression the nation has very justifiably risen as one man, to vindicate the original contract subsisting between the king and his people. To resist the king's forces by defending a castle against them, is a levying of war: and so is an insurrection with an avowed design to pull down all inclosures, all brothels, and the like; the universality of the design making it a rebellion against the state, an usurpation of the powers of government, and an insolent invasion of the king's authority. But a tumult with a view to pull down a particular house, or lay open a particular enclosure, amounts at most to a riot; this being no general defiance of public government. So, if two subjects quarrel and levy war against each other, it is only a great riot and contempt, and no treason. Thus it happened between the earls of Hereford and Glocefter in 20 Edw. I. who raised each a little army, and committed outrages upon each others lands, burning houses, attended with the loss of many lives: yet this was held to be no high treason, but only a great misdemeanor. A bare conspiracy to levy war does not amount to this species of treason; but (if particularly pointed at the person of the king or his government) it falls within the first, of compassing or imagining the king's death.

There's just no ambiguity here. The goal of the January 6th attack was to overthrow the government! By sacking the seat of that government! It's as clear a case as you could ask for.

Confusion is introduced, I think, by the idea that Trump honestly thought himself the rightful president. Set aside whether that man is capable of honest thought: this is simply irrelevant. The supporters of Bonnie Prince Charlie sincerely thought him the rightful king of England. But they were still charged, and some of them hanged, as traitors. It just doesn't matter. Believing that you are the rightful king is not a legal justification for rising up in arms to vindicate that claim. Blackstone addresses this directly, when he notes that there is already a forum for pressing this sort of claim: Parliament.

The other source of confusion is that Trump's "army" was not very, y'know, impressive. The idea that a few thousand MAGA idiots could fight the United States of America feels, well, insane. (Notwithstanding that the mob did in fact get pretty damn far.) But this is also just not relevant! The Treason Clause doesn't require that you levy effective war against the United States. For the obvious reason that, as Alexander Pope famously wrote, if treason doth prosper, none dare call it treason. If people are allowed to make war against the government right up until their forces represent a genuine threat, then the government will find itself genuinely threatened. The law is entitled to insist, as it does insist, that nobody make even a sorry effort to fight the state.

I have never heard a persuasive counter-argument. It seems that our political culture just ignores the notion that Trump is an actual, factual traitor, because that allegation is so far out of bounds of contemporary American society. But the January 6th attack was equally far out of bounds. It was the first time anyone had seriously levied war against the nation since the Civil War! It came terrifyingly close to succeeding in its goal, which is commonly described as "disrupting the peaceful transfer of power" but is in fact nothing less than the overthrow of the government.

He will never be prosecuted for treason, at this point. And it has no real legal relevance otherwise: the Fourteenth Amendment only requires "rebellion or insurrection," not treason as such (though the latter must necessarily also qualify as the former, I should think). But Trump is a traitor, and we should say so, if only to shame the devil.