Juries!

Welcome back to a special bonus edition of Constitutional Perspectives!

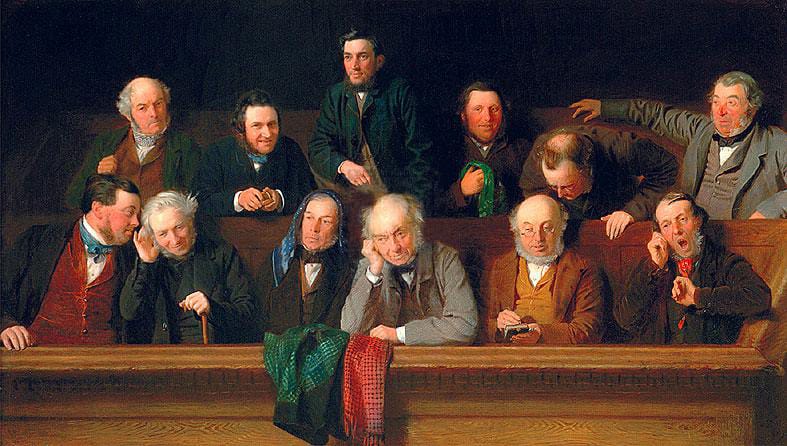

The last installment covered the power, structure, and character of the federal judiciary. But I realized that I left something out. I told you all about the judges. But our country has another kind of judicial body as well: the jury. I had meant to say a little bit about juries last time, perhaps in the section on the common law (for juries are a defining common law institution). But I forgot. So today you're getting a supplemental lesson that's all about juries.

So, what's a jury? In brief, it's a group of citizens, typically numbering in the low double digits, who are chosen to serve some function in the legal system. You might etymologically think that this is just the same "jur-" root that means "law," as we saw with "jurisdiction." And it is, kind of, but indirectly. The Latin ius (law) was also the root of iurare, meaning to swear (as an oath). A juror, then, is one who is sworn. And a jury is a group of these. Jurors are lay citizens who take a special oath (to do impartial justice, mostly) and who are thereby constituted as a quasi-governmental body.

In their ancient origins – by "ancient" here I mean like, England a thousand years ago, yes you heard me right, a thousand – juries had a broad and eclectic assortment of powers. This included things like investigating crimes, but was by no means limited to that. They would also play a function not altogether unlike what we would today think of as a congressional committee hearing, investigating some policy concern and recommending solutions. These juries would serve for some substantial length of time, maybe a year, and were one of the main institutions of local governance.

Today they have a rather more specialized function. Our system has two kinds of juries: grand and petit. (We don't usually actually call petit juries by their full title.) "Grand jury" sounds very, well, grand, but what these words actually connote is the literal size of the jury. A grand jury has, typically, twenty-three members. A petit jury, classically, is twelve, but can be even smaller than that.

Grand juries are the heirs to the ancient general-purpose juries, but they basically only serve one purpose now: charging people suspected of criminal offenses through what we call indictments. Grand juries, like their forebears, serve for extended periods of time, and will hear many requests from prosecutors to issue indictments over the course of their service. The government will present their evidence, both that a crime has been committed and that a particular person committed it. Then, typically by majority vote (hence the odd number of jurors), the jury decides whether the government has shown "probable cause" to charge that person. Grand jury proceedings are exceedingly secret, basically to protect the reputation of anyone against whom an indictment is sought but not issued.

Petit juries, therefore, are also known as trial juries, or just "juries," because they're the ones with a public profile. Each petit jury is chosen – empaneled – to hear a specific case. Jury service – on grand and petit juries alike – is a civic obligation; when you receive a "jury summons," you must show up at the courthouse on the date specified. Not everyone who is summoned is actually chosen to serve as a juror, however; the process of "jury selection," also known as voir dire, involves questioning potential jurors to make sure they are suitable for the case in question (e.g., that they don't know one of the parties). These questions can result in a potential juror's being dismissed "for cause" by the judge, but also each of the parties to the case will typically have some number of "peremptory strikes" that they can use to exclude some number of potential jurors without having to give a reason.

Once the jurors are chosen and sworn, they sit through the trial, watching as each side presents their evidence and make their legal arguments. Then, after all the evidence has been presented and the judge has instructed the jury on the law, they go off to discuss who should win the case. (We say they "retire" for "deliberations.") These deliberations are also exceedingly secret; there is almost no circumstance in which a juror can be compelled to reveal the contents of deliberation.

The "stats" on petit juries can vary. The classic version has twelve jurors and must deliver a unanimous verdict. If, after deliberating for a reasonable length of time, they can't all agree – a so-called "hung jury" – the judge will have to declare a "mistrial," which basically means that the trial has to be done again from scratch with a new jury (assuming the prosecution/plaintiff feels that's worth the trouble). Juries in federal criminal cases are required to meet these traditional standards. And the Supreme Court recently ruled that state criminal juries must be unanimous in order to convict. But in civil cases in federal court, and any kind of case in state court, the jury is not constitutionally required to have twelve members. Nor are civil juries constitutionally required to reach unanimous verdicts.

Okay, so, why do we do this? After all, juries are expensive! The jury trial system requires ordinary citizens to take significant periods of time off from their normal lives. This is why many states prefer to use smaller juries, which reduces these costs. But it would be cheaper still just to dispense with the juries altogether and let the professional judges do the deciding instead. Why don't we? The civil law system, used in places like France, traditionally didn't have citizen juries at all. And many procedure scholars think that professional judges would do a better and more accurate job of deciding cases. I've heard that one leading scholar once remarked that, if he were innocent, he would rather be tried by a judge, but if he were guilty, he would want a jury. Not ideal!

There are, I think, a couple of reasons, beyond just that it's an inheritance from our eighteenth century forebears that we're stuck with because it's in the Constitution. (I'll talk about the right to trial by jury when I get to the Bill of Rights.) The most important is that, at the Founding, juries were understood as a democratic institution that could play a significant role in resisting tyranny. Without juries, the decision whether to e.g. put someone in jail is made entirely by government officials: prosecutors and judges. If the state is corrupt and oppressive, those officials might effectively conspire to deprive people of their liberties unjustly. The jury interposes a group of ordinary citizens between the awesome might of the state and those who are subject to it. This doesn't matter much if the government is professional and honest. Events of recent days, however, are reminding us that it can matter quite a lot when the government itself becomes the enemy of freedom.

Juries also have a curious kind of role to play in the common law system. Basically, they allow the law itself to essentially punt on certain kinds of questions. Negligence, for example, is an enormously important concept in tort law. People are, generally, obliged to use due care to avoid injuring other people, and if they fail to do this, they may be found negligent and liable for damages. Okay, what's due care? Well, it's the degree of care that a reasonable, ordinary person would use in that situation. Okay, and what's that? Answer: uhhhh whatever the jury says! Because jury deliberations are secret, and juries – unlike judges! – do not have to give reasons for their decisions, these kinds of questions can be placed inside a kind of black box, and we never have to develop actual doctrine to answer them. (In describing this function, I do not especially mean to be endorsing it; it's just a fact of how our legal system works.)

Finally, contra the opinion of that procedure scholar I alluded to above, I've seen some studies suggesting that the biggest difference between how lay juries decide cases and how professional judges would decide them is that the juries take the concept of "proof beyond a reasonable doubt," the standard used in criminal cases, much more seriously. Judges, who have seen hundreds of very similar cases, have a tendency to become jaded and assume that defendants are guilty. But each jury is chosen anew, and sees the evidence with a fresh, and therefore somewhat more critical, eye. This is the main reason why I personally like the jury system, or at least, it was until the "resisting tyranny" part suddenly became very relevant.

Okay, back to our regularly scheduled programming.