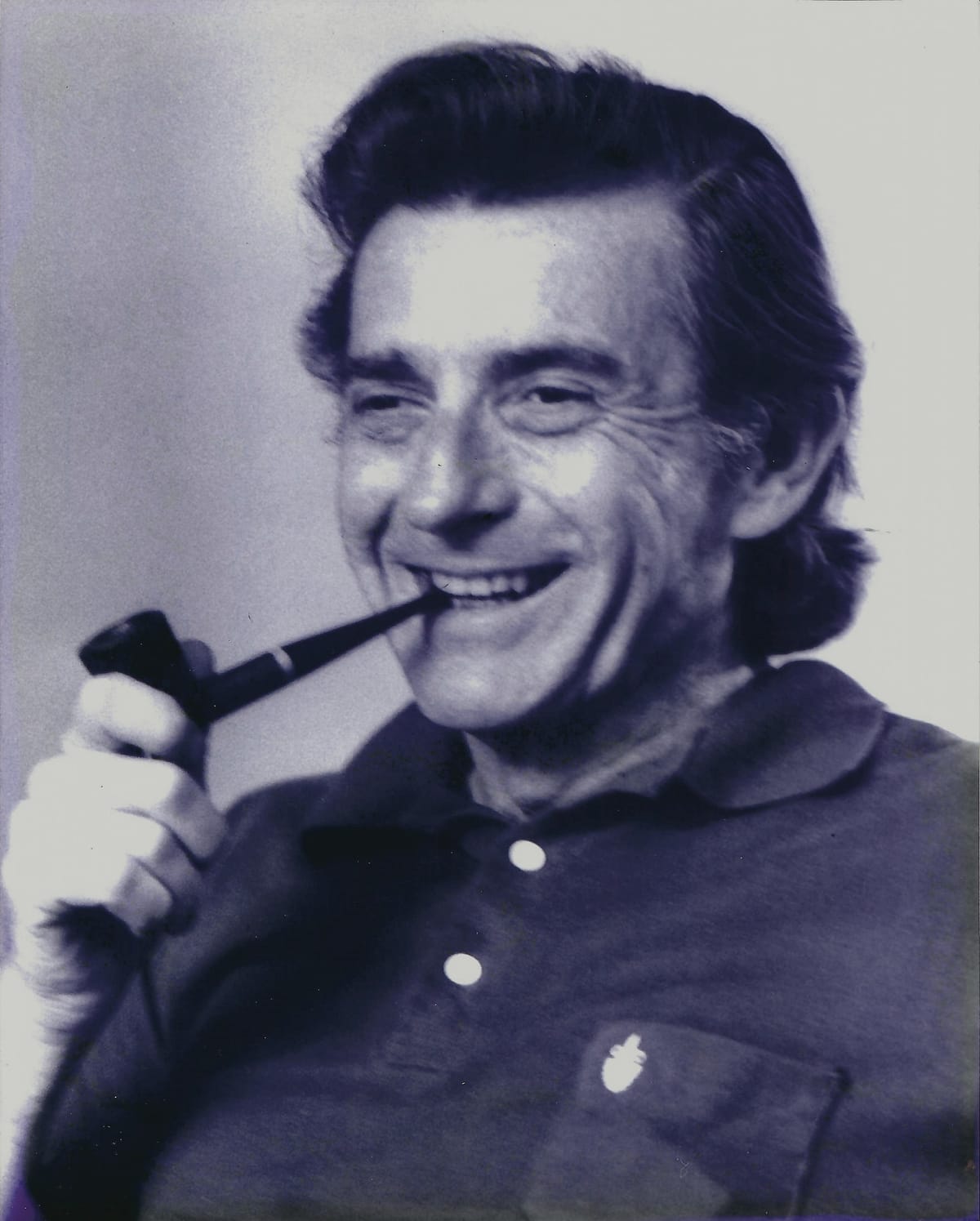

My Grandfather, Charles Black

If you listen to me talk about constitutional law for long enough, you are going to hear the name Charles Black. He is the single greatest influence on my thinking about law and political philosophy; he also happened to be my grandfather. I want, therefore, to write a short piece about who he was and the influence he had on me and the broader world of constitutional law, and to give a basic sense of his major works (and some more minor ones that I happen to be aware of).

He was born in Austin, Texas in 1915. His parents were, as I understand it, relative liberals on matters of race. Of course, in segregated Texas that just meant that they didn't really care about race issues one way or another. Still, their indifference likely helped pave the road for their son's outright apostacy. As he always told the story, that apostacy began on October 12th, 1931, when he happened to see Louis Armstrong perform at a dance in Austin. "It is impossible," he wrote much later in life, "to overstate the significance of a sixteen-year-old Southern boy’s seeing genius, for the first time, in a black." (Apologies for the old-timey phraseology there, a constant minor issue when quoting his work.)

As a result, he came to see the central organizing principle of his society as a lie. And as a result of that, he left, and after a series of misadventures that I don't really know the details of, ended up as a law professor at Columbia University. It was in that milieu that he came to be a part of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund – the first member of the organization who was neither black nor Jewish – just as the legal campaign against segregation was reaching its climax. At LDF, he worked on Brown v. Board of Education (1954), and his name was one of about a dozen on the NAACP's brief in Brown II, the companion case decided the following year.

Shortly thereafter he moved from Columbia to Yale, which is where he really made a name for himself. He became one of the preeminent constitutional scholars in the country, and together with Alexander Bickel helped make YLS into a constitutional law powerhouse. He taught an awful lot of prominent people at Yale, notably including one Hillary Rodham (as she was) – Bill also took some of his courses but never stood out as much, as I hear the tale. His protégés also included Akhil Amar and Philip Bobbitt, through whom I am his grand-student as well as his grandson.

Eventually he moved back to Columbia, where his wife, the legal historian Barbara Black, promptly became Dean – the first female Dean of any Ivy League law school. By the time I knew my grandfather, he was an old man, and not in the best of health after a lifetime of smoking his pipe. I was young enough when he died, in May 2001, that I never had a chance to talk with him about his work, one of my life's great regrets. What memories I do have of him are fond ones, and his death was the first great sadness in my life.

It should not go unsaid that he was a complicated man, even a broken one in many ways, for all that he accomplished. Childhood abuses had turned him into the kind of person who couldn't manage not to hurt the people closest to him. I never really saw that side of him, a grandchild's privilege I suppose; much of what I know about his demons comes from this incredible essay by my aunt Robin, one of my favorite things I have ever read.

His life is, I think, a perfect example of something the Eleventh Doctor says, that the good things in life don't always soften the bad things, but by the same token neither do the bad things spoil the good ones or make them unimportant. He was an abused child and an emotionally neglectful parent. He was a bit of a renaissance man: he wrote poetry, painted, played the trumpet, spoke Icelandic.

Oh, and he was a genius.

If you listen to just about anyone talk about his scholarly work, you'll hear pretty much the same thing: that he had a singular kind of clarity, moral clarity, analytical clarity, that was just unmatched by any of his contemporaries. Most of his great writings are short, and written in an extremely accessible style. He saw straight through to the heart of things; more, he believed in seeing through to the heart of things, in not letting artifice obstruct the truth of what mattered. And what mattered, in his mind, was race. His experiences as a civil rights lawyer informed his entire body of work; he saw achieving racial equality and extirpating race from American public life as the central task of constitutional law.

I'll close this piece out with a brief overview of his corpus of work. I recommend every single piece that I'm about to mention to anyone with an interest in American constitutional law, in the absolute highest of terms; they are all utterly formative for me.

The Lawfulness of the Segregation Decisions (1960): ten-page essay defending the Brown case, from Herbert Wechsler among others. To my mind, and many others', this remains the most compelling account of Brown ever written. Practically every line from this essay is an absolute banger; I quote it constantly.

Structure and Relationship in Constitutional Law (1969): His most influential work within the world of constitutional theory. If you've read my primer on the modalities, you're already a bit familiar with the ideas in this book: he was the original theorist of what he called the "method of inference from structure and relationship."

Capital Punishment: The Inevitability of Caprice and Mistake (1974): This, on the other hand, was probably his most famous work with the lay public. Written at the height of the death penalty debate, during the national moratorium imposed by Furman v. Georgia (1972). Avowedly not a legal or constitutional argument, nor even a moral one exactly: instead it focused on, well, the inevitability of caprice and mistake – ideas with which I think we're all much more familiar now than most people were at the time.

Impeachment: A Handbook (1974): Written during the Nixon impeachment, this one has been reprinted twice, because uhhh, it keeps coming up?? Considered by many the authoritative guide to all things impeachment; recall that in 1974 there hadn't been a presidential impeachment in over a century. Members of Congress will read this to tell them how to do impeachment hearings.

The People and the Court: Judicial Review in a Democracy (1960): A personal favorite; I've been known to call this my favorite political theory tract. Written two years before Bickel's more famous The Least Dangerous Branch. Anticipates and answers the so-called "countermajoritarian difficulty" with judicial review. Also highlights the essential work that judicial review does in maintaining legitimacy in a system of limited government powers.

Perspectives in Constitutional Law (1961): This one's a little more obscure. It's essentially a treatise on constitutional law, but... a very short one. Essentially a handful of musings on the state of constitutional law in the midcentury. Has a bunch of fascinating nuggets in it; if you ever see me going on a rant about how the New Deal was totally constitutional under status quo ante precedent, I'm getting it from this book.

Decision According to Law (1981): Another obscure one. This is where he engages most directly with legal realism, where he defends against realist skepticism the idea that "decision according to law" is a real and meaningful concept. I see this book as laying the foundation, in many ways, for Bobbitt's theory of constitutional jurisprudence. Indeed, I think that this attitude toward legal realism is a huge part of what distinguishes their intellectual tradition.

The Occasions of Justice: Essays Mostly on Law (1963): Does what it says on the tin. This is an essay collection, and as such doesn't have a single topic or theme. But many of the essays are quite interesting, among other things just as an artifact of what American public life was like in the early '60s.

A New Birth of Freedom: Human Rights, Named and Unnamed (1997): His last major work, and the only thing on this list written while I was alive. Argued that we should understand the Ninth Amendment to incorporate by reference the Declaration of Independence, and in particular the rights to "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness," and that this would be a much stronger foundation for American human rights law than the doctrines fashioned by the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court, 1966 Term, Foreword: "State Action," Equal Protection, and California's Proposition 14 (Harvard Law Review, 1967): Unlike everything else in this list, this one is dense and deeply technical. At a 30,000-foot level, you can see this article as outlining a choice between two different conceptions of what law is responsible for: does the Constitution only forbid the state from itself imposing racial oppression, or does it rather oblige the state to use all the tools at its disposal to ensure racial equality? Needless to say, his preferred answer was quite different from the one given by the Supreme Court. There's a lot of stuff in here, even just in the opening passages, that presaged a lot of what we now think of as "critical race theory," all the subtle ways that racism insulates itself from any mechanism of redress or accountability.

If you're interested in reading more about him, from a variety of other perspectives, the Columbia Law Review published all of the speeches from his memorial service, which you can read here. There's also this piece, by his student Avi Soifer. And probably more I'm not aware of off the top of my head.