On the Law that Applies to Impeachment

This is a post that I am writing simply because it seems to need saying, and I feel like I am going to keep having occasion to reference it.

Earlier today, Rep. Al Green (D-TX) forced a vote on an article of impeachment against Donald Trump. He does this sort of thing a lot. As typically happens, the vote failed. The interesting wrinkle this time is that twenty-three House Democrats voted against the resolution (to "table" it, in technical Congress-speak), and 47 Democrats besides voted "present," neither supporting nor opposing the resolution. This latter group included much of House leadership, which put out a statement explaining why they didn't support Green. Plainly, leadership is annoyed that Green is not cooperating with their overall strategy. But that's not the point.

The point is that this has all brought impeachment into the public Discourse. And, as always happens whenever we're talking about impeachment, I get people telling me that I'm a fool for trying to talk about the law that ought to govern impeachment proceedings. Perhaps not in so many words, but I'll make some comment about Congress's obligations under the law, and someone (often several someones) will chime in to tell me that, since the verdicts in cases of impeachment cannot be appealed to the law courts, Congress can do whatever it wants.

Every time, I say the same thing, and I am frankly sick of typing it out over and over again. So I am just going to write up my response here, with somewhat more coherence than a microblogging format can permit.

First of all, it is true that judgments in cases of impeachment cannot be appealed to the Supreme Court, or to any other court outside the Senate itself! The Senate has "the sole Power to try all Impeachments," and the word "sole" is taken to imply that its judgments cannot be appealed. There has never been a case of successful appeal to the law courts; the one time anyone tried, Judge Walter Nixon's effort to claim the Senate had used an improper trial procedure (namely referring the matter to be tried in committee, and having the full Senate vote based on that committee's report) the Supreme Court rightly said that it had no power to intervene.

Nixon v. U.S. concerned the procedures used in the Senate, but the same point assuredly holds as to the substance of the thing. Article II, Section IV lists the impeachable offenses as "Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors." That last category is open-ended, and reasonable people can disagree about whether the conduct at issue is a high crime. The Senate's determinations on this matter are final. Absolutely final. Nixon left open the possibility that maybe, in the truly outer limit, the courts would have some power to step in and say that the Senate had not really conducted a trial. There is no such exception on the substantive side. The courts have no business saying that, despite the two-thirds vote to convict, the accused was not actually guilty of an impeachable offense.

But so what? Plenty of government officials act without the threat of judicial reprimand. Many of them nevertheless take care to act in accordance with the law as they understand it. Notably, this includes, y'know, the Justices of the Supreme Court, whose rulings can no more be appealed than the Senate's judgments in cases of impeachment. No one thinks it is good enough for the Supreme Court to say "because I said so," in explaining its decisions – certainly not the Court itself! To the contrary, it always acts by analyzing the relevant legal materials that bear upon the case at hand. Of course they do not always get it right. And when, in my judgment or that of any other observer, they get it wrong, their decisions are nonetheless binding and authoritative. But they are obliged to try their best to follow the law. We all understand that, were they to disavow this obligation – perhaps by, hmm, deciding major cases without issuing any kind of written opinion at all? – this would be a bad thing; it would be grounds for criticism.

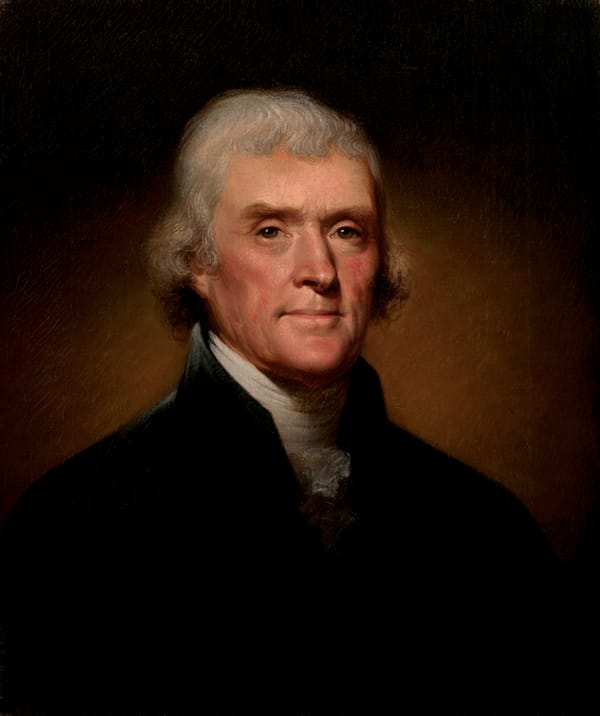

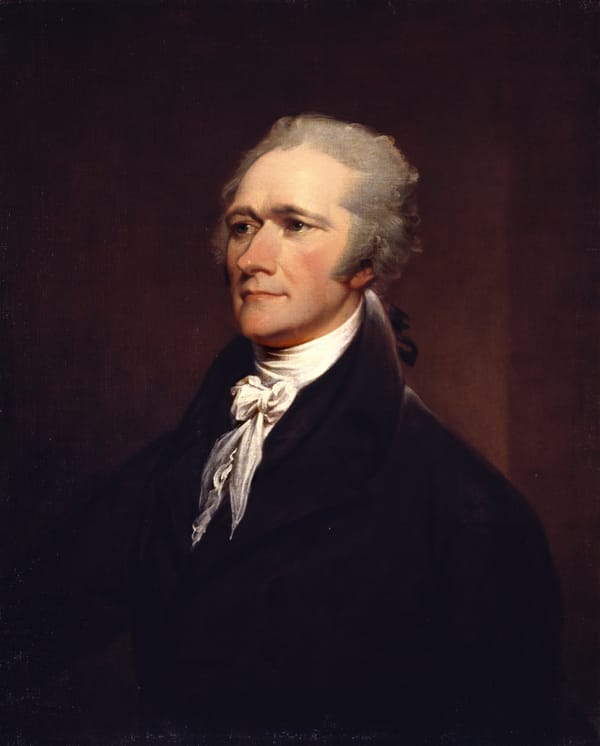

The executive, too, often must act in cases where there is no meaningful judicial supervision. In 1934, President Roosevelt created the (much misunderstood) Office of Legal Counsel, precisely for these situations. OLC exists to ponder the legal obligations faced by the executive, whether or not those obligations are judicially enforceable. Indeed, recognition of this freestanding duty to follow the law goes all the way back to the Founding. Consider the debate between Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton and Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson over whether President George Washington should sign the bill creating the First Bank of the United States. At the time, it was thought the president could only properly veto a bill if he deemed it unconstitutional. Of course, if he did veto on other grounds, there would be no recourse, except possibly a congressional override. But he took the obligation seriously, asking for the legal views of his chief counselors.

There is simply nothing incongruous about a government official asking what the law requires of them, even when there is no judge looking over their shoulder. This is not really different from what the judges do themselves! One feature of the modalities of constitutional argument is that they are accessible to all, whether they are a judge, a government official, or a member of the public. Any government official, in contemplating the law that applies to them in some situation, can always ask "what would I say if I were a judge and this case came before me." They have access to all the same legal materials.

Now, sometimes the law gives an official unfettered discretion to act. Contra the Founding-era understanding I was just mentioning, I think it quite clear that the President may properly veto legislation for any reason at all. Is impeachment like that? Absolutely not. Admittedly the constitutional materials are not detailed. But a standard is provided: high crimes and misdemeanors. This is no more inscrutable than other constitutional standards like "due process of law" or what-have-you. Their meaning is to be determined, as the need arises, through the ordinary tools of legal interpretation, i.e. through the use of the modalities.

And although the standard for impeachment is framed in general terms, the language actually gives us quite a lot to go on in making particular determinations. There is clearly something of the criminal; the sense is that an impeachable offense is just that, an offense, an act of wrongdoing. But at the same time, we know (for various reasons) that "high crimes and misdemeanors" is not limited to the commission of ordinary crimes. It's really not that hard to do the analysis in particular cases, though of course reasonable people will always disagree around the edges.

All of this is true for the procedural questions as well. Both the House and the Senate have a fair amount to go on, as they try to figure out what their role is supposed to be. We can ask questions like: is the Senate to be bound by the House's determinations of law? In other words, must the Senate accept that the offenses charged are impeachable offenses, and limit its role (as a trial jury would be limited) to determining whether those offenses actually occurred as a factual matter? This came up during the Clinton impeachment, when Senators objected to being referred to as "jurors" (because it implied exactly this kind of limited role). Chief Justice Rehnquist rightly upheld this objection, for the Senate is in fact entitled to judge the law as well as the facts.

This is just one example. The point I was arguing about tonight is another: must impeachment involve extensive factual hearings? The correct answer to this question is "no," and this answer comes to us principally, I think, from the prudential modality. Sometimes the disputed points will be factual in nature, and when this is the case, the presentation of evidence will be needful. I think the command that the Senate is to "try" impeachments suggests that they are in fact obliged to take witness testimony, examine documentary evidence, make determinations of credibility, etc. where such evidence is relevant to the case before them.

But where the facts are basically not contested, and the issues in the case are legal (i.e., is what the President did actually an impeachable offense or not?), then evidentiary hearings serve no purpose. Why make everybody go through the farce of presenting evidence to prove a bunch of factual allegations that aren't even contested? Indeed, unlike in an actual criminal case, the Senate has broad discretion to decide how much evidence it needs to prove particular facts. Suppose that the President is being impeached for something they said in public. I think in such a case, they would very likely just stipulate to the facts, and fight solely on the law side. If they refused to do this, then I suppose some evidence might be needed – but not necessarily very much. Again, this happens to be what I was arguing with folks about just now, but it is meant here just as an example. It is not that hard to do legal reasoning about these questions; the Constitution gives us plenty to work with.

I think much of the reluctance to say that the impeachment process is bound by any kind of law comes from the legal realist mindset. Oliver Wendell Holmes famously wrote that a legal duty is "nothing but a prediction that if a man does or omits certain things he will be made to suffer in this or that way by judgment of the court." As there are no consequences that can possibly befall the Senate for its conduct of impeachment trials, it cannot be said to labor under any kind of legal duty in that conduct. The House can suffer only one consequence (that the Senate may refuse to convict), but the only "duty" this could support is the duty to bring charges that the Senate will be inclined to convict on. This philosophy of law leads people to Gerald Ford's famous statement that "an impeachable offense is whatever a majority of the House of Representatives considers it to be at a given moment in history." (Of course we have already seen that Ford is wrong about this, if only in that the final judgment belongs to the Senate, not the House.)

The thing is, though, Holmes's formulation rests on seeing the law in a certain way. As he writes,

If you want to know the law and nothing else, you must look at it as a bad man, who cares only for the material consequences which such knowledge enables him to predict, not as a good one, who finds his reasons for conduct, whether inside the law or outside of it, in the vaguer sanctions of conscience.

And I think it is simply unreasonable to take this "bad man" approach when we are talking about the conduct of impeachment trials. Congress is not supposed to act like a Holmesian bad man! Members of Congress are, after all, oath-sworn to "support and defend the Constitution." In my view, this must entail that they should not knowingly take or support any actions which are, in their own view, counter to the Constitution. To do so is to violate their oath of office.

This obligation is heightened in the impeachment context! The Constitution says expressly that, when sitting as a court of impeachment, the Senators are to be "on oath or affirmation." That oath, in actual practice, has always been to "do impartial justice according to the Constitution and laws." If they are thinking like Holmes's bad men, they forsake this oath. And the very function of impeachment is to hold public officials to account for abusing their power, for breaking their oaths. How can a Congress which does not itself act with honor possibly stand in judgment of others' misdeeds?

Finally, it is not quite true that there is no appeal from a court of impeachment. In our system, there is always appeal to the People. The Constitution always envisions that the People are the final judge. This is not just a power that the People have, but a responsibility. If we are committed to the task of collective self-government through law, then we must demand that our chosen representatives follow the law and honor their oaths. We should demand that Congress act with honor in all cases of impeachment, that it follow the law of impeachment to the best of its ability. Where we see that it has fallen short of this duty, we should visit consequence upon it at the next election. In saying that there is no law that applies to the impeachment process, I think we are letting ourselves off the hook. We can hardly be surprised at what must inevitably follow.