Slavery, Part II: From Necessary Evil to Positive Good

Welcome back to Constitutional Perspectives!

Last time, we covered the sordid history of American slavery, up though the Philadelphia Convention of 1787. I talked about all the ways – some pretty apparent, some more subtle – in which the "peculiar institution" of slavery shaped the U.S. Constitution. Today I'll be telling the story of slavery in the early American Republic, from the Founding through the 1830s. Why the 1830s? You'll see.

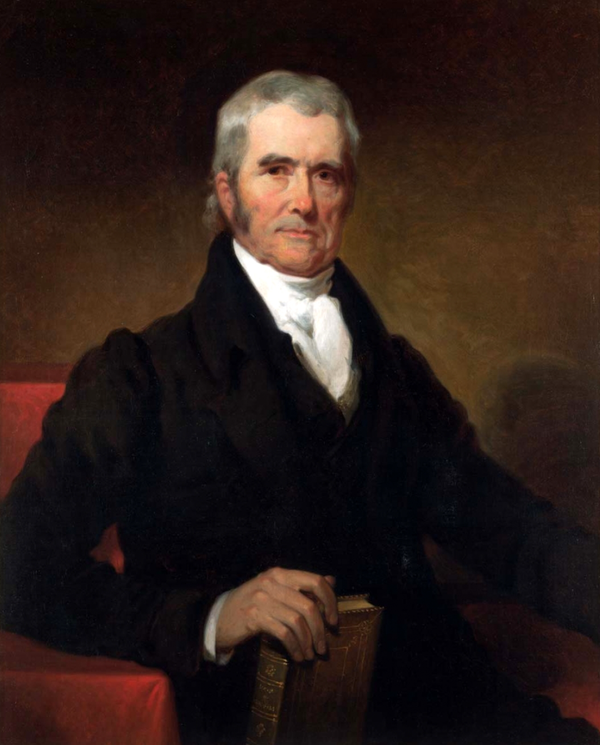

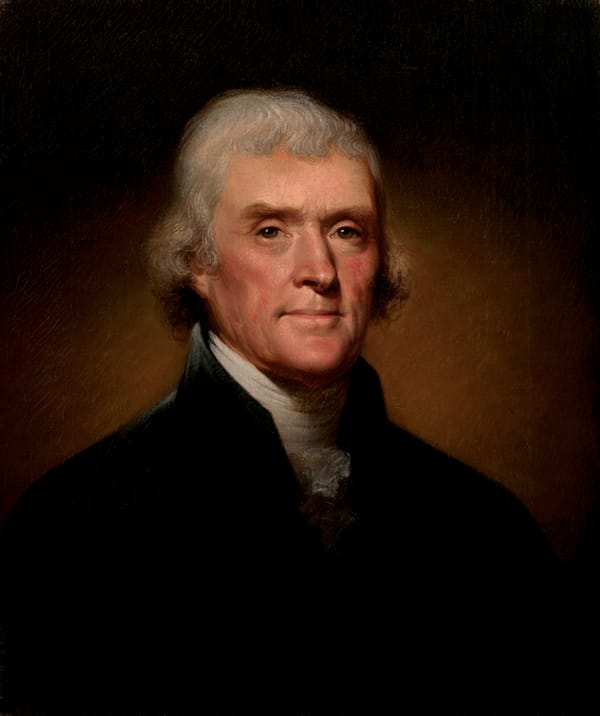

Now, at the very beginning, in what historians might call the early Republic or the First Party System, slavery was not a big issue in national politics. The Federalist Party included most of the Northern abolitionist types. But it also had a Southern wing, in particular a South Carolinian wing. So even someone like John Adams, a moralizing, Puritanical fellow who despised the institution, could not really make anti-slavery advocacy a part of his political agenda. Conversely, while the Jeffersonian party was led by a bunch of, y'know, slavers, like Jefferson and Madison, these men were not especially pro-slavery in their philosophical views. As of 1789, they would mostly have been pretty happy to see the institution wither away over time.

And, in 1789, it was pretty easy to see that happening. Indeed, the terms of the Founding compromise held, with little controversy, just about as long as the Founding generation held the reins of political power. In 1808, exactly as soon as the Constitution allowed for it, President Jefferson signed a bill banning the foreign slave trade, which the political class abhorred pretty much without exception. The ill-fated Hartford Convention, wherein the battered remnants of the Northern Federalist Party met in 1815 to discuss their grievances with the terms of the Union and with President Madison's conduct of the War of 1812, proposed an amendment removing the Three-Fifths Clause among several others, but was not mostly about slavery. In fact the result of that Convention was the death of the Federalist Party altogether, the death of the First Party System, and the brief national hegemony of Jefferson's Democratic-Republican Party.

The issue just could not stay buried forever, though. All the while, two factors had been simmering in the background of national politics, making it inevitable that we would start fighting over slavery before too long. One was Eli Whitney's 1793 invention of the cotton gin. I mentioned earlier that the economy of the South was largely organized around plantations, worked by slaves, growing cash crops like tobacco. Well, the cotton gin made cotton king, and ensured that these plantations would remain economic powerhouses for the foreseeable future.

The other factor was westward expansion. The Constitution left the question of slavery to the states. It also provided for new states to be admitted to the Union. The young nation had a bunch of land out west that wasn't really a part of any of the existing thirteen colonies, although it was largely claimed by one or more of those colonies. The plan was for this land, as it became increasingly populated (by white Americans, rather than natives), to be organized first into territories and then into states, admitted to the Union on equal terms with the original thirteen. Each new state would have a constitution, and each new state constitution would either permit or prohibit slavery within that state.

The Northwest Ordinance, first issued by the Continental Congress in its waning days in 1787 and then re-affirmed by the United States Congress in 1789, had organized all the western lands north of the Ohio River into a single "Northwest Territory." It also forbade slavery within this territory, except "in punishment of crimes whereof the party shall have been duly convicted." This set the geographic rule that would govern the admission of new states during the early Republic: those north of the Ohio River were admitted as free states, while those south of the river were admitted as slave states.

This rule maintained a balance in the admission of new states. Vermont was the first to join, in 1791, as a free state. (Indeed, Vermont has always been the strongest bastion of antislavery sentiment in the entire country.) One year later, parts of Virginia's western holdings became Kentucky, a slave state. In 1796, Tennessee became another slave state, but in 1803 the free state of Ohio joined. As most of the North had abolished slavery by this point, this alternating pattern also maintained an overall national balance of power, with the Senate always just about evenly divided on issues of slavery.

Something else happened in 1803, however: the Louisiana Purchase. President Jefferson was able to acquire an enormous tract of land, to the west of the country's existing borders, running from New Orleans on the Gulf coast all the way up to land that is now part of Canada. Suddenly there was much, much more land that seemed destined to be admitted to the Union down the road. And, in particular, there was a lot more land down South. The Northwest Territory contained the land that would eventually become Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin, four more free states. Down South, though, there was only a small plot of land west of what we now know as the state of Georgia, much of which was claimed by Georgia. The addition of Louisiana, and then of the formerly-Spanish Florida territory after General Andrew Jackson conquered it in 1818, gave the South a lot more room to grow.

Louisiana itself – the state, not the massive French holding – was admitted, as a slave state of course, in 1812. Indiana, a free state, followed in 1816. Then Mississippi (slave state, 1817), Illinois (free state, 1818), and Alabama (slave state, 1819). As 1820 dawned, there were eleven slave states (NH, VT, MA, RI, CT, NY, NJ, PA, OH, IN, IL) and eleven slave states (DE, MD, VA, NC, SC, GA, KY, TN, LA, MI, AL), a perfect balance. But trouble was brewing west of the Mississippi. The remnant of the great Louisiana Territory had, after the admission of its tiny southeastern corner as a state of the same name, been renamed as the Missouri Territory. Then the southernmost portion became the Arkansas territory. Then the southeastern portion of what remained sought admission as the State of Missouri, and the whole thing kicked off.

The thing about the state of Missouri is that, although it was (mostly) located north of the Ohio River, it had never been a part of the Northwest Territory. Slavery had never been banned there, and it seemed natural (to some) that it be admitted as a slave state. The North flipped its lid at the prospect. This would not only have violated the implicit rule that had prevailed since the Constitution's adoption, it would also have thereby tipped the balance of power in favor of the slave South. But the South would not accept admitting Missouri as a free state: partly because it would tip the balance in favor of the North, but also partly because they increasingly saw slavery not as a necessary evil that would hopefully go away soon but as an economic powerhouse institution that they hoped to expand across the continent.

The result was the Missouri Compromise of 1820, engineered by Speaker of the House Henry Clay. Missouri was admitted as a slave state, but, at the time, the discontinuous northern portion of Massachusetts became the free state of Maine. This preserved the balance for the time being. Simultaneously, Congress also passed the so-called Thomas Proviso, named for Illinois Senator Jesse Thomas, banning slavery in the remaining western territories north of Missouri's southern border (the so-called 36° 30' parallel). Missouri, in other words, was declared to be a one-time exception to the geographic pattern, not a precedent for the northern expansion of slavery. And the expectation of Senate balance was maintained into the far future.

The Missouri Compromise would hold for thirty years; its demise, and the Compromise of 1850 that replaced it, set the stage for the chaos that became the Civil War. In the interim, the country settled into the Second Party System, with national politics divided between the Democrats (originally defined as supporters of President Andrew Jackson) and the Whigs (originally his opponents). Both parties had Northern and Southern wings, and on the issue of slavery in particular, a Northern Democrat was more like a Northern Whig than a Southern Democrat, and mutatis mutandis for the other configurations. On the whole, the Whigs were somewhat more anti-slavery. But it was never a defining element of the Whig party platform, nor of partisan contestation during this entire age. The Missouri Compromise sort of worked. Well enough, anyway.

So what happened to tear it apart? There are basically two important moments in this thirty-year period when slavery mostly had a low national salience. The first was a confluence of several events in the old South around 1830. In August 1831, a man named Nat Turner led a slave rebellion in Southampton County, Virginia. The rebellion ultimately failed, and after several weeks of pursuit, Turner was caught and hanged. But he had killed something like sixty white Virginians along the way, and had utterly terrified the rest. Astoundingly, many white Virginians actually had the clarity of thought to suggest gradual abolition/emancipation, essentially realizing that maintaining a state of perpetual war with one-third of their population was a bad idea. They, uhhh, they lost the argument.

Meanwhile, trouble was brewing in South Carolina. In 1828, Congress had passed an extremely stiff tariff bill. Styled the "Tariff of Abominations" by its detractors, the law had the effect of favoring the Northern economy (which produced, and exported, manufactured goods) over the Southern (which produced raw materials, like cotton, and had to import their manufactures). Well, all tariffs had that effect, and were therefore supported by the North and opposed by the South. But the 1828 tariff was especially severe. An 1832 tariff bill eased off the 1828 rates to a degree, and also thereby eased the concerns of much of the South.

But not the South Carolina planter elite, a.k.a. the single worst element in American antebellum politics (by a lot). They remained implacable, and were led by Vice President John C. Calhoun into what we now call the Nullification Crisis. This crisis is going to take center stage when I get to Level Two and begin talking about the debate over the nature of the Union; Calhoun in the principal villain of that story. The reason why I am mentioning the Nullification Crisis now is that it had an outsized effect on the development of racist thought in this country.

The planter class wanted to pass something called an Ordinance of Nullification. This would have declared the federal tariffs null and void within South Carolina. The ordinance drew on Calhoun's constitutional theories, but today my concern is not for the legal theory of the matter but for the politics. I keep saying it was the planter class that wanted this. But the thing about rich people is that there are never all that many of them. To get what they wanted, the planters needed the support of the white yeoman farmers, who made up the mass of actual voters in South Carolina as in much of the South. (A few years earlier they might not have had to care about the yeomen, but Andrew Jackson had brought a populist tide into American politics and had drastically expanded the franchise. Oops.)

Now, as it happens, the economic incentives facing the yeomen were quite a bit different than those facing the planters. I don't actually remember the economic details, but they are, again, not really important here. What is important is that the planters needed the yeomen's votes, and how they contrived to get them. The pitch was all about racial hierarchy. The yeomen might be poor, the planter class and its mouthpieces said, but they were not at the bottom of the totem pole. No, that position was held by the Negro slave. And it always would be, as long as the planters maintained their political dominance. They would defend the system of racial hierarchy for all time, thus giving the poor whites someone to look down on. Didn't that sound nice?

It should also sound familiar. The Nullification Crisis was the crucible that forged the racist ideology that would dominate the nation for, well, the rest of its history, so far. Together, the events in Virginia and South Carolina circa 1831-32 saw the creation of the "positive good" ideology, which saw slavery as, well, a positive good. Even the slave-owners of the Founding generation had known that slavery was monstrous evil, that they were violating the sacred human rights of these men and women, just as they were claiming them for themselves. Positive good theory held that the African slaves had no human rights, that they were not human, not really. It was for their own good to be held in bondage, as they were not fit to rule themselves. And it was certainly good for the world that these savages be enslaved, lest they prove a danger.

Concomitantly, the institution of slavery became worse. Not that it had been good before, mind you. But the levels of barbarism and wanton cruelty began to ratchet up. In the wake of Turner's rebellion, many states began making it a crime to teach a slave to read – fearing what dangerous ideas the slaves might get into their heads, if they knew how to have ideas. Violence against slaves became ever more pervasive and severe. Any sense that these were people, with some kind of dignity that demanded some kind of recognition even amidst the terrible injustice of slavery itself, faded away. They were animals, who could only be controlled through violence and pain.

In 1830, the idea that slavery might just go away with time still seemed plausible. Virginia itself was considering going the way of New York and Pennsylvania, adopting a gradual abolition scheme, very much as Washington and Jefferson might have hoped would someday happen. And if Virginia had put itself on the road toward freedom, the entire national balance would very likely have tipped against slavery for good. By 1833, though, this prospect was dead. The South was caught in the fever grip of racial terror and deliberately-engineered bigotry. There was, at this point, probably no way to avoid what was coming.