Slavery, Part III: The Breaking

Hello and welcome back to Constitutional Perspectives!

Finally, finally, our story is going to reach the breaking of the Constitution that became the American Civil War of 1861-65. I initially thought that both of the last two lessons would have covered this entire period, but it turns out there's rather a lot to say about slavery and the Constitution.

We left off last time in 1833, when a pair of crisis – Nat Turner's Rebellion in Virginia and the Nullification Crisis in South Carolina – had seen the birth of the "positive good" strain of pro-slavery ideology in the South. At the national level, though, slavery was not especially high salience in the Age of Jackson. As I mentioned, the parties – Democrat and Whig – were not polarized north vs. south, and neither had an especially strong position on slavery.

This began to change in the 1840s. The biggest culprit was the Mexican-American War, a central project of President James K. Polk. Elected on a platform of aggressive territorial expansion in the West, Polk quickly delivered with the 1845 annexation of the then-independent Republic of Texas. But Texas had outstanding boundary disputes with Mexico, and once Texas became part of America, these disputes pretty quickly turned into causus belli. We won the war, quite decisively, and acquired not only the disputed areas in Texas but essentially all of what is now the Southwestern United States – Arizona, California, etc.

Much as Missouri had done a generation prior, all this new territory threatened to upend the delicate balance of slave versus free states in Congress. Texas was admitted as a slave state, and the newly acquired territories were all south of the dividing-line under the Missouri Compromise. However, unlike in Texas, slavery was not already present in these newly acquired territories (having been abolished in Mexico by the Constitution of 1824). Representative David Wilmot of Pennsylvania tried to put language in an appropriations bill that would have kept slavery out of these territories, the so-called Wilmot Proviso. He didn't succeed. Suddenly the national balance of power was tipping toward the Slave Power.

The Slave Power had a grievance of its own, though. In 1844, the Supreme Court had decided a case called Prigg v. Pennsylvania. The case concerned the capture of fugitive slaves. Pennsylvania claimed that a man named Prigg had come up north and kidnapped people who were not actually fugitive slaves. Prigg argued that Pennsylvania could not prosecute him for performing a federal function under the 1789 Fugitive Slave Act. The Court sided with Prigg. But along the way, Justice Joseph Story (himself no particular friend to slavery) included some cryptic language suggesting that, while Northern states could not prevent slave-catchers from operating within their territory, nor neither were they obliged to lift a single solitary finger to help them.

The Northern states got the message, and immediately began making life as difficult as possible for the slavecatchers. It is after Prigg that we begin seeing the pattern of Northern mobs freeing supposed fugitive slaves from custody and the like. And the South was livid. The North, as they saw it, was betraying the core tenets of the national compact!

All of this came to a head in the Compromise of 1850. Brokered by Daniel Webster, a Whig from Massachusetts, and Stephen Douglas, a Democrat of Illinois, this new compromise had five or so key elements:

- California was admitted to the Union as a free state;

- Texas ceded a significant portion of its northern and western lands to the federal government, taking on the iconic shape we know today;

- The territories of Utah and New Mexico were organized out of the remaining lands in the Southwest, and would be permitted to choose whether or not to allow slavery under the principle of popular sovereignty;

- The slave trade (though not slavery itself) would be banned in Washington, D.C.; and

- The Fugitive Slave Act of 1789 was replaced with a new, much harsher measure, that among other things created a vast new federal slavecatching bureaucracy.

The last of these turned out to be the most important. The 1850 Fugitive Slave Act dominated the politics of the 1850s. The North simply could not abide it, as they felt it made them complicit in the South's crimes against humanity. Instead of resolving the conflict created in the wake of Prigg, the new act intensified it, a lot. Several times during the 1850s, the Supreme Court had to step in to prevent Northern states from interfering with slavecatchers.

The other time bomb in the Compromise of 1850, which did not take very long to go off, was the use of "popular sovereignty" to decide on the status of slavery in the new Southwestern territories. This was Douglas's idea, and he was keen to replicate it in the other territories. Like Kansas and Nebraska. Which, unlike Utah and New Mexico, were north of the Missouri Compromise line. Douglas's Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 organized these two new territories, and provided that each might choose for itself whether or not to permit slavery, thus repealing the Compromise of 1820.

The result is known as Bleeding Kansas. Nice going, Stephen! Pro- and antislavery forces poured into the territories and fought an incredibly bloody battle to determine whether they would become slave or free. It was essentially a little civil war within the Kansas territory, and it lasted right up until the same state of affairs engulfed the whole nation. Indeed, there's an argument for dating the start of the American Civil War to 1854, rather than the more conventional 1861.

All of this put an end to the Second Party System, and to the Whig Party itself. Northern Whigs were just done with a party that could not take a strong stand against the moral abomination of slavery. Antislavery forces began meeting up in the weeks and months after the Kansas-Nebraska Act's passage, mostly in the Midwest, and these meetings eventually gave rise to a whole new political party: the Republican Party. Its platform expressly opposed slavery, and, while not claiming any power to force Southern states themselves to abolish the institution, envisioned the use of national power at every available opportunity to oppose the spread of slavery. The Republicans nominated John C. Fremont, a famous Western explorer who had briefly been one of the first Senators from California, for president in 1856, and Fremont carried eleven northern states. The only previous antislavery political party in the country, the short-lived Free Soil Party, had never carried a single state, despite running former President John Quincy Adams in 1848. The Republican Party was a sea change in national politics.

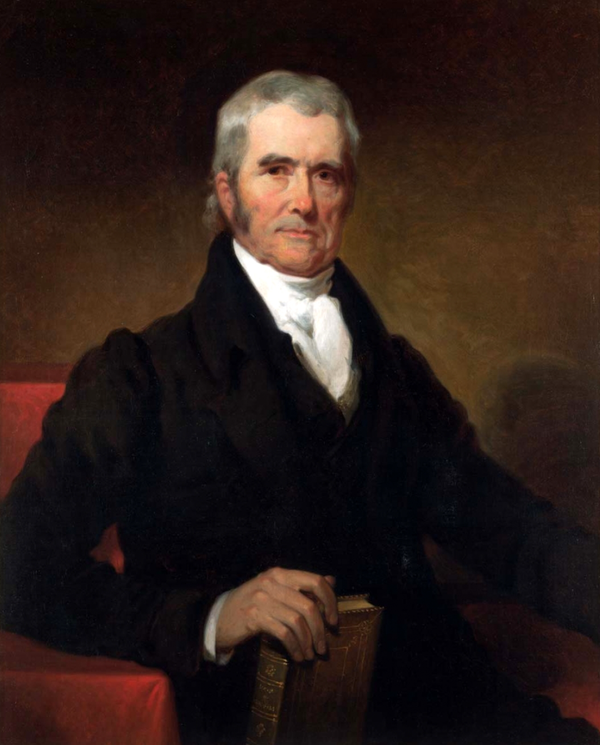

Still, Fremont lost the 1856 election to James Buchanan, Democrat of Pennsylvania. Though a Northerner, Buchanan was ardently proslavery (a so-called "Doughface"). At his inauguration in March 1857, Buchanan made a cryptic remark about how the Supreme Court was about to settle the issue of slavery in the territories once and for all. It turns out he had been whispering with Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, at the time a highly respected jurist, about a case currently pending before the Court. An unusual case, involving a corner-case application of the rule of Somerset's Case (i.e. that a slave brought by their master onto free soil became free by operation of law). Taney, we now know, went back from the inauguration to the Court and tore up the existing draft opinion, which would have decided the case on narrow, technical grounds.

In its place, he wrote the worst decision the United States Supreme Court has ever issued, a case whose name instills terror and revulsion to this day: Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857). The underlying substance of the case was the claim by a black man, Dred Scott, to have become free when his master, Dr. John Emerson, brought him first to Illinois (a free state) and then to Wisconsin (a free territory – the land in question now being a part of Minnesota) in 1830-36. Subsequently Emerson had taken Scott back to St. Louis, in the slave state of Missouri, and it was in the St. Louis county courts that Scott sued for his freedom.

For various bullshit reasons, the Missouri courts (which did acknowledge the basic Somerset principle!) ultimately denied the suit. Essentially, they said, Scott would have had to sue for his freedom in the Illinois courts while present in Illinois; once he had returned to Missouri, it was too late. Thus, Scott sued again in federal court. He could do this because his (supposed) now-owner, John Sanford, the brother-in-law of Dr. Emerson, had moved to New York. And as you may recall, the federal courts have jurisdiction over cases between citizens of different states – so-called "diversity" jurisdiction. The trial court, relying on Missouri law, reached the same conclusion as the Missouri Supreme Court had done, and Scott appealed to the Supreme Court.

Taney could easily have just affirmed for substantially the same reasons. That would have kept poor Mr. Scott in bondage, but we would not today know or remember the entire episode. Instead, acting at least in part at President Buchanan's request, he went big. His opinion for the Court reached the following two monumental holdings:

- No person of African descent could ever become a citizen of the United States, or of any State (and therefore the federal courts were without jurisdiction to hear Scott's suit); and

- The Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment forbade the application of the Somerset rule within the federal territories, as the rule would deprive slaveowners of their "property" without due process of law.

I will explain, in exhaustive detail, why both holdings are extremely wrong as a matter of law when we get to Level Two. For present purposes it is enough that the ruling happened, and that it made it essentially impossible to avoid civil war. Of course the North was outraged. The Court had, in a stroke, declared the Missouri Compromise, the very basis of national unity for thirty years, unconstitutional! It had brought the vile institution of slavery to every single federal territory. Oh, and there was every reason to suspect it would soon rule that even free states could not insist upon the Somerset rule. As a certain Illinois lawyer who had served one term in Congress back in the 1840s put it,

We shall lie down pleasantly dreaming that the people of Missouri are on the verge of making their State free; and we shall awake to the reality, instead, that the Supreme Court has made Illinois a slave State.

Oh yeah, his name was Abraham Lincoln. This quote comes from his "House Divided" speech, given on June 16th, 1858 at Springfield, Illinois; you should probably just go read the whole thing. This speech, as well as his famous debates with Douglas (the principal architect of the whole mess, really) during the 1858 Illinois Senate race, made Lincoln the preeminent national spokesman for the Republican Party and its governing philosophy.

Although Lincoln lost the Senate race, he won the nomination for president in 1860, facing off against Douglas (on the Democratic ticket) as well as John C. Breckingridge (on the breakaway "Southern Democratic" line) and John Bell (for the "Constitutional Union" party). Where Bremont carried eleven states, Lincoln carried eighteen, and won the presidency. Douglas, running, again, on the ticket of the oldest political party in the world, carried but a single state: fittingly, Missouri.

Of course the South was not about to take Lincoln's ascension lying down. They had become pleasantly accustomed to having the federal government on their side during the 1850s. Lincoln's protestations that he had no desire to interfere with their "domestic institutions," that in fact he supported amending the Constitution to this effect, fell on deaf ears. South Carolina promptly called a convention to discuss secession, i.e. leaving the Union altogether. That convention unanimously adopted a declaration of secession on December 20th, 1860. The rest of the Deep South followed suit within the next couple of months.

President Buchanan made no effort to stop the South from leaving, famously just allowing the Union to fall to pieces while Lincoln was waiting to take the reins. There were various efforts over the winter to stop the onset of war. Senator John J. Crittenden of Kentucky proposed yet another "Compromise," which Lincoln could not support as it would not have halted the spread of slavery. A peace conference was held in February in Washington, to no avail.

How could any of these efforts have succeeded? The country had already come apart, over the prior ten years. The idea that the Union could be maintained on its current terms was simply a fantasy. There was no mutual trust or accord; instead, the entire nation had become engulfed in conspiracism and violence. Bleeding Kansas literally hadn't stopped; the antislavery Wyandotte Constitution for the State of Kansas was only approved by Congress after a bunch of the Southern States had seceded (and therefore withdrawn their congressional delegations). The violence reached Congress itself, in the famous 1856 incident of South Carolina Representative Preston Brooks savagely beating antislavery Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts with a cane. Oh, and in 1859, abolitionist radical John Brown – who had cut his teeth in Bleeding Kansas – raided the armory at Harper's Ferry, Virginia, in an attempt to spark a slave revolt throughout the South. The raid failed, and Brown was hanged, but as with Nat Turner's Rebellion nearly thirty years prior, the South was spooked.

Anyway. Lincoln took office on March 4th, 1861, and delivered his First Inaugural Address (which I will be spending a lot of time on in Level Two), a stern rebuke of the constitutional theories of secession. Lincoln's first item of business as president was trying, desperately, to keep control of all remaining Union forts in the South, something President Buchanan had not bothered even trying to do. On April 12th, Southern forces – or "Confederate" forces, as by now the states that had left the Union had come together to create their own Confederate States of America – fired on Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina. Three days later, Lincoln called for a force of 75,000 to suppress what he saw as the ongoing rebellion in the Southern states. In response to that, the remaining slave states of the Upper South – Arkansas, Tennessee, North Carolina, and (crucially) Virginia – joined the Deep South in seceding and joining the Confederacy.

The war had come.