On The Nature of the Argument Against Humprey's Executor

Everyone's talkin' 'bout the removal power this week!

And there's no mystery why: on Monday, the Supreme Court held arguments in a case called Trump v. Slaughter, about whether the president can fire an FTC commissioner at will. From the tenor of the oral arguments, as well as from like, the entire trajectory of the last four decades of conservative legal thought, it seems pretty clear that the landmark 1935 decision Humphrey's Executor v. United States – about, wouldn't you know, whether the president can fire an FTC commissioner at will – is done for.

The question of removal powers – who has the power, under our Constitution, to fire executive officials of various ranks and forms – is the signature issue of something called "unitary executive theory." This is an idea, advanced by the conservative legal movement since the early Reagan years, that the Constitution vests all executive power in the President, and that Congress is therefore sharply limited in its ability to insulate any part of the federal executive from direct presidential control. Typically, although this is by no means implied by the phrase "unitary executive" itself, this is also paired with an aggressive vision of the scope of executive power as a whole.

Reams have been written about this topic already, including by many people who have done actual research. But I want to write a little bit on the subject, just because I think this is a good question on which to use Philip Bobbitt's six modalities of constitutional argument. In particular I think the nature of the arguments on the issue are often quite misunderstood, and that correctly apprehending their modal character can illuminate the matter. So I want to walk through each of the modalities and what they have to say on the matter.

We can start with the text. What does the Constitution itself have to say on the matter? Ha ha, trick question, it doesn't say anything. Article II, Section 2, Clause 2 says that the President "shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States, whose Appointments are not herein otherwise provided for, and which shall be established by Law." But it doesn't say anything about how those officers, once appointed, are to lose their positions. Of course there are things in the text that can form the basis of arguments about the removal powers, but the text does not speak directly to the issue, at all.

How about the historical modality? This, recall, concerns the intentions of the Founders. So, did the people who wrote and/or adopted the Constitution have an understanding on the matter of removal, even though they didn't write it into the document? Lolnope. As far as I am aware, this was just an oversight, plain and simple. It just did not occur to the delegates at Philadelphia that this was something they needed to address. Nor do, say, the Federalist Papers speak directly to the issue. Again, there's stuff in the Papers that seems like it might bear on the matter, notably Hamilton's encomium in Federalist 70 to "energy in the executive." This can plausibly form the basis of a structural argument on the matter. But I don't think it counts as a historical argument as such, not unless we are claiming that Hamilton (or someone else at the time of ratification) had specifically thought about the removal question and had an answer in mind.

It is precisely for this reason that the removal power question makes such a great example, to my mind, of how the Constitution is not just the text. The Constitution, understood as a written legal instrument, simply does not speak to the matter. And yet, this is clearly a question of constitutional law, and one that demands an answer. Even if we want to say that, whereas the Constitution places no limits on the subject, Congress has an entirely free hand in the matter, that is a conclusion about constitutional law. We must answer the question, the answer must be a rule of constitutional law, and the answer cannot be found in either the text or the original intent. This highlights how the Constitution is a framework for decision-making, as well as a written legal instrument. There are all sorts of questions like this, where the Constitution gives us the question but leaves us to craft the answer – though most are not as important as this one.

And in fact I think the argument for a broad presidential removal power is, and has been, first and foremost a doctrinal argument. This makes sense, given what I have just said, because doctrine is one of the two modalities (the other being prudence) that is native to the kind of common-law context I was just describing. Where there are decisions that must be made, the doctrinal mode tells us, the important thing is that they be made consistently, according to principled, general rules rather than ad hoc favoritism. By resolving issues as they arrive in this principled fashion, we gradually build a body of law that supplements those answers that the Constitution itself provides.

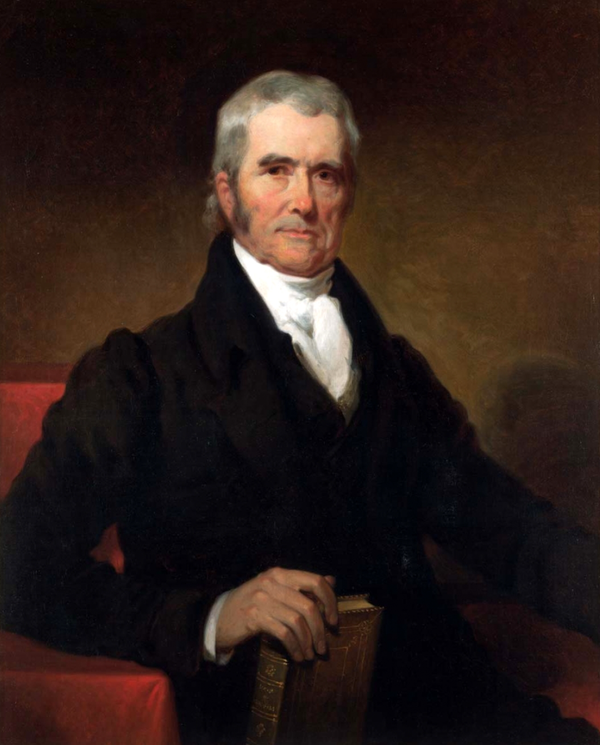

The claim, then, is that although the Constitution does not answer the removal power question, the question has been decided, and it has been decided in favor of presidential power. Typically this argument focuses on the so-called Decision of 1789: the First Congress immediately had to confront the issue of removal, because most of its first Acts were establishing one government department or another. There was a debate in the Congress on the matter, and as a result Congress gave the President the power to fire Cabinet secretaries at will. There is at least some reason to think that it did so on the view that this was what the Constitution required, that if Congress had, say, tried to reserve a role for itself in the removal of executive officers, it would have overstepped its bounds.

Because this happened in 1789, and because James Madison was involved (in his capacity as a Representative of Virginia), there is a tendency to see this as the basis for an historical argument. But that's wrong. Strictly speaking, nothing that happened after the moment of ratification matters for doing historical argument. Sometimes we may point at post-ratification practice as evidence of pre-ratification intent. But here, we know that there was no pre-ratification intent, that the First Congress was confronted with the issue precisely because the Convention had forgotten to address it. If the Decision of 1789 matters, then, it matters in its capacity as a precedent, not unlike a judicial precedent even though it was Congress who made the decision.

And of course, in the intervening two centuries, that decision has been adhered to almost without exception. The one exception, to my knowledge, is the Tenure of Office Act, adopted by the Reconstruction Congress to prevent Andrew Johnson from firing cabinet officials and thereby undermining the Reconstruction effort. Johnson was impeached for violating the Act, and acquitted in part because there were doubts as to the Act's constitutionality. And if the Constitution itself left this question open for future decision, it is hard to deny the weight of two centuries of unbroken practice following a decision in the First Congress.

However! There are a few problems with this doctrinal argument, as a doctrinal argument. For one thing, in the last few years there's been a wealth of historical scholarship suggesting that this way of characterizing the practices in the early Republic is just wrong. Flat-out, factually wrong. See, for example, this recent article by Christine Chabot. There is even reason to doubt the understanding of the Decision of 1789 as a constitutional decision all. On the contrary, some scholars now suggest, it was purely a policy matter; Congress did not conclude that it was obliged to give the President an unlimited power to remove even the Cabinet secretaries.

But there's another problem, perhaps a deeper one. As has often been pointed out, one function of the "originalist" philosophy is to justify overruling major judicial precedents in the name of an older, and therefore "true," understanding. But this only makes conceptual sense if the older understanding is actually a part of the pre-ratification understanding. If the game we're playing is a doctrinal one, on the other hand, then the later precedent must prevail over the earlier one. Although we strive for consistency in adjudication, it is nonetheless true that a decision-maker is not strictly bound by its own prior decisions. Rather, the rule is that a decision must be adhered to until repudiated.

Even if we take the Decision of 1789 to have set a precedent on the removal power question, then, we must also take the adoption of statutes like the Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914, which gave the commissioners of the new agency a fixed tenure subject only to removal "for cause," as having modified that earlier precedent. Not as having overruled it, exactly: the Progressive Era Congresses that gave tenure protections to the newly created regulatory agencies did not go after the President's power to fire Cabinet secretaries as such. And Humphrey's Executor, the case that's about to be overruled, observed this distinction, holding only that the President's constitutional power of removal (which had been recognized in Myers v. United States nine years prior) did not extend to multimember regulatory commissions like the FTC. And if we're doing doctrinal argument, it is simply incoherent to attack Humphrey's Executor by invoking the Decision of 1789. The later controls over the earlier.

Now, there are three other possible modalities in which the argument for presidential removal powers could be couched. Prudence, as so often, allows for arguments on both sides. The unitary executive folks have their arguments: a good rule of thumb is that any time you hear someone talking about "accountability," in the context of a constitutional law argument, they're talking prudence. The idea is that giving the President control over the entire executive branch will make it easy for the People to understand whom to blame for things. The problem with this is that it proves too much: this critique runs against the entire scheme of divided government powers. Indeed, it is an argument disturbingly reminiscent of the arguments made by German scholars of administration in the 1930s, that the best way to organize the government was to put the business of administration entirely in the hands one man, a singular Leader, whose will alone would dominate the government. We call this the Führerprinzip. It's a Nazi idea. It's bad.

Conversely, it is simple enough to argue that tenure protections for regulatory agencies is prudent insofar as it gives space for the apolitical use of expertise. And, if we fear that these "experts" might go off on their own agenda rather than the public's, well, that's what Congress is for. Every decision made by an administrative agency may be overturned by statute. This is, as Jamelle Bouie points out, the fundamental lever of democratic accountability for the administrative state.

The unitary executive folks also make a structural argument. This, I think, is the right way to understand what they mean by invoking the Article II Vesting Clause and the Take Care Clause. The idea is pretty simple: the Constitution creates a unitary executive. On some level, this is indisputable. Hamilton does use the word "unity" in Federalist 70, and, look, "The executive Power shall be vested in a President." It really does say that. They could have set up an executive council; they didn't. Executing the laws is the President's job, and theirs alone.

Now, as I said in Constitutional Perspectives, the President does almost none of this job with their own two hands. Rather, they execute the laws primarily by appointing people who actually go around doing the work of executing the laws. But these people are to be understood as acting on the President's behalf; they are, as we say, the "hand of the President," they are the tools by which the President carries out their duty. And if this is the case, then the President must be able to choose their own tools. Similarly, it is impossible for the President to "take care that the Laws be faithfully executed" if they are not the one doing the executing – or at least, if they do not have the power to supervise those who are.

I think there's something to this! But I was also realizing earlier today that the argument doesn't go as far as the unitary executive folks want it to. Because the thing is, yes, executing the laws is the President's job. But that job, by nature, involves being subservient to Congress. In Hamilton's famous formulation of the nature of the three branches, the executive has FORCE; it is Congress that has the power of WILL. Executing the laws is not meant to involve the exercise of the president's own will. And if this is correct, then when Trump says he is firing so-and-so because they do not support his agenda, he is overstepping the proper bounds of his role as the chief executive. It is not his agenda which ought to matter, but Congress's.

Following this line of thought, I think the Take Care Clause argument suggests a pretty straightforward test. Yes, the President must have the power to remove other executive officials if they fail or refuse to faithfully execute the laws – in other words, if they defy the will of Congress. Any statute providing "for cause" removal protection must include this as valid "cause" for firing somebody. However, if the statute does include this in the definition of "good cause" (and I'm pretty sure they all do), then it does not offend the Take Care Clause in the slightest. Easy.

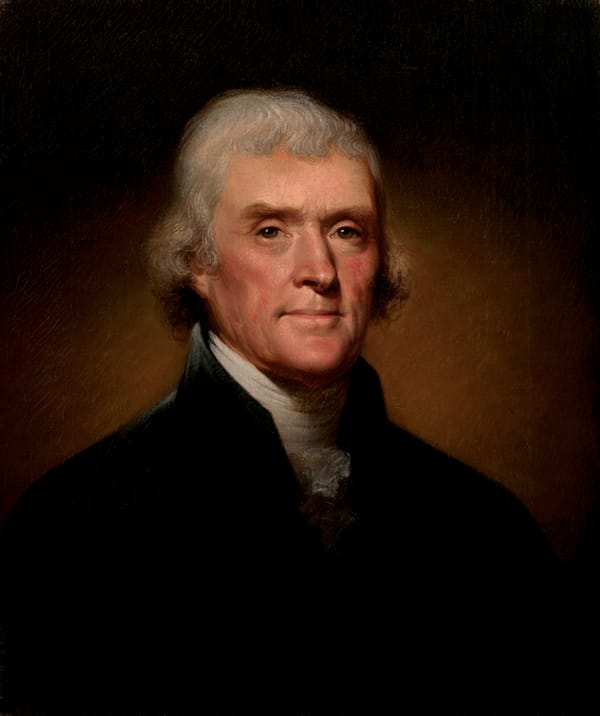

Now, there's one last modality that I have not yet mentioned. As so often, ethical argument is saved for last. I don't think any of the existing Discourse around the removal power issue is really speaking in an ethical register. But I do think there is something to be said, and it may ultimately be the strongest basis for a claim of strong presidential power here. Put simply, the character of the American Presidency has changed, a lot, since the days of George Washington, in a whole bunch of ways. There are a whole bunch of facets to this change, from the increasingly popular and democratic business of presidential elections to the rise of the administrative state itself, America's changing place in world affairs, and even the development of nuclear weapons. I am not going to get into all of this in full detail here.

But suffice it to say, I think you can make a strong argument that what I was just saying in the previous paragraph about how the President's job is not supposed to involve the exercise of their own will is just not really true anymore. What exactly that entails about the question of removal powers, I am not certain. But I suspect the advocates of presidential power in that domain would have more material to work with if they embraced the idea that this is a new development, rather than trying, implausibly, to claim the mantle of the Founders.