Slavery, Part I: The Ugly History

Welcome back to Constitutional Perspectives!

We left off last time on an ominous note. There's something missing from my discussion of the Constitution so far, something lurking in the shadows. You can see the same thing, the same shadowy presence, in the Constitution itself. Scattered throughout the document are a bunch of, you might say, rather cryptic provisions.

Article I, Section 9, clause 1:

The Migration or Importation of such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit, shall not be prohibited by the Congress prior to the Year one thousand eight hundred and eight

Huh?? "Such persons?" What persons?

Article IV, Section 2, clause 3:

No Person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due.

Weird! What's going on here?

Well, the original language of Article I, Section 2 on congressional apportionment offers a clue:

Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons.

Ah. What are these "other Persons"? Well, they're not "free Persons." They're not free.

They're slaves.[1]

Famously, that word does not occur anywhere in the 1789 Constitution. But the "peculiar institution" of racial chattel slavery is woven through the entire thing. It is the original sin of the American Republic, and it is what tore the Republic apart a mere seventy years after the Constitution was adopted. To this day, the fallout of that breaking is what defines the constitutional order.

So let's talk about slavery.

Slavery is a very old, basically universal practice throughout human civilization. Ancient Athens, renowned as the origin of democracy, had a slave class that lacked the political rights of citizens. And in a way, the concept of "slavery" only really comes into focus when someone, somewhere has the idea of political freedom. In a world of pure might makes right, there's nothing that distinctive about it. Early modern political theory regarded the practice of enslaving the losers of a war as, basically, beneficent: after all, the victors could have just slaughtered them all. (John Locke at least limits this to those who prevail in a "just" war, which, in his defense, I think he understood to be quite a rare case.)

American slavery was a different animal. It may not quite be true to say that it was the worst form of slavery that had ever existed anywhere on the planet, but it was unusually bad in a number of ways. We call it "chattel" slavery, a word that means, like, physical possessions ("movable property" is the technical definition I think, it's everything except real estate a.k.a. land). The American slave system purported to consider the enslaved as chattels, property, rather than any kind of human person. Also, American slavery was hereditary. It wasn't just a system whereby some could be bound to serve others against their will; it was a system of hereditary caste where a whole class of society was bound to service through the generations. And of course that caste system was thoroughly racialized: black Africans were the slaves of white Europeans.

This unusually vicious form of human bondage grew out of the Transatlantic Slave Trade that grew up in the wake of Christopher Columbus's 1492 expedition to China the Americas. As transatlantic navigation became commonplace, so did transatlantic trade. And, around this same time, European explorers made contact with the people of subsaharan West Africa. There, they acquired slaves, sometimes by conquest and capture but also via trade. There was plenty of that normal, universal kind of slavery in West Africa at the time, and the Europeans had plenty of goods that the West African societies wanted to trade for. But from Africa, the European ships would then sail across the Atlantic with their human cargo, who were wanted to work the sugar plantations of the Caribbean – work so miserable that you literally could not pay people to do it. Finally, the ships would sail back to Europe with raw goods from the Americas, completing the so-called "triangle trade." When, a little over a century after Columbus, the first outposts of British North America were established, they brought African slaves with them, essentially as a matter of course.

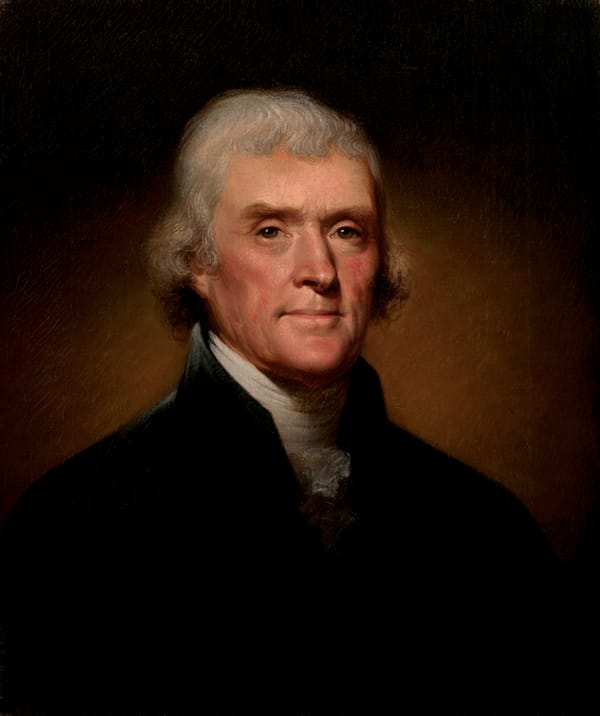

By the time of American independence, the global practice of slavery was already starting to decline. As the liberal-democratic age began to reshape the globe, people started to think, wait a minute, this is kind of horrific. In 1772, the great English jurist Lord Mansfield decided Somerset's Case, which held that a slave brought to England immediately became free. Slavery was so "odious," Mansfield said, that it could only exist by "positive law," i.e. by statute. Within July 1776 itself, many American slaves and their advocates were arguing that the recent Declaration of Independence, with its language of universal natural rights to life and liberty, must necessarily be taken to have abolished slavery. And in many northern states, the courts agreed! This was the primary basis on which slavery was abolished in the North, as courts looked to the analogous language in their own states' newly adopted constitutions.

Ah, but slavery was just not that important to the societies of these Northern states. It never had been, even though it had always been present there. The South was another matter. Recall how I said that the sugar plantations of the Caribbean were so miserable you could not get anyone to work there of their own free will? The same was true, basically, of the plantations in the American South. The South, as you may know, is basically one big swamp. It's hot and sticky and broadly inhospitable, at least before the invention of modern air conditioning (1901). The land just is not suited to subsistence agriculture. But it was suited to growing a variety of cash crops, notably (in the preconstitutional era) tobacco.

The entire society of the American South, therefore, depended on its African slaves. It could never have come into being without the institution of slavery: that was the only way to run the tobacco plantations. And there was no way in hell that the South was going to let Jefferson's rhetorical flourishes about why the King of England was a tyrant destroy their entire way of life. The same arguments that flourished in the North got nowhere in the South. So, by the time of the 1787 Philadelphia Convention, America was already divided between free states in the North and slave states in the South. (The dividing-line was, more or less, the Mason-Dixon line, a.k.a. the southern border of Pennsylvania. New York and New Jersey abolished slavery only gradually; no state south of the line abolished at all.)

People will talk about the drama of the Constitutional Convention in "large state vs. small state" terms. This is, at best, a very partial truth. New York, one of the other "big states" along with Virginia and Pennsylvania, was quite hostile to the nationalist ambitions of the Virginia Delegation. (Well, the senior New York delegates were, anyway, in keeping with the wishes of Governor George Clinton, who would become a leading Anti-Federalist. But they literally left town a few weeks into the thing, leaving junior delegate, erm, Alexander Hamilton to represent New York. ) Slave against free was every bit as important a divide. The reason we don't focus on it as much is the way the compromise went down.

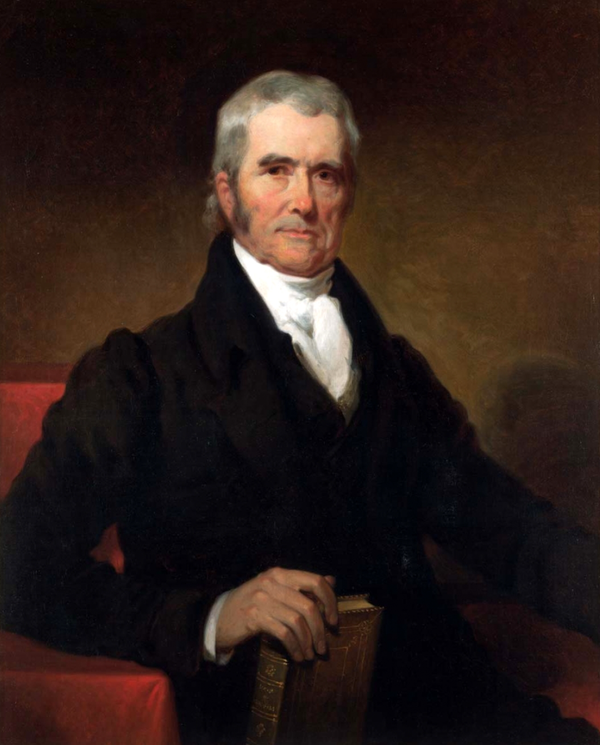

You can imagine putting the twelve states at the Convention (Rhode Island didn't show) on a kind of political alignment grid. Massachusetts, for example, was a fairly large state, and the most anti-slavery of them all. The other New England states were similarly anti-slavery, but were much smaller. New Jersey was moderate on slavery, and a leader of the "small state" pack. Virginia, on the other hand, was also kind of moderate on slavery; although it was very much a slave state, the political elite (of 1787, anyway) all deplored the institution and hoped to see it fade away within a few generations. But it was the leader of the nationalist, "big state" pack.

Then you had the Deep South. The thing about the Deep South, Georgia, South Carolina, and to a degree North Carolina, is that they actually were genuinely pro-slavery, in a way that the Virginia delegation wasn't. They were also small! At the time anyway. Georgia had only 82,000 residents at the 1790 census; Virginia had nine times as many. And in a way, the Deep South was the key to the whole Convention. One way to think about how it all went down is that Virginia and Pennsylvania, the driving forces behind the whole thing (along with honorary clique member Alexander Hamilton), forged a pact between Massachusetts and South Carolina. Massachusetts got what it wanted: a strong national government. The price, though, was giving South Carolina what it wanted: a pro-slavery Constitution.

And it is a pro-slavery Constitution.[2] I have a lot of respect for Frederick Douglass's efforts to argue the contrary view, and I'll talk about them later in this series because I think he's doing some very interesting things in terms of constitutional theory. But it's just not actually correct as a matter of law. There isn't any real ambiguity to it. The concerns of the slave states are accommodated not only in the provisions I quoted up top. In a number of places, provision is made for the Union to suppress domestic insurrections within the states. You think that didn't mean slave revolts? It absolutely did; the Declaration itself had referred to slave uprisings as domestic insurrections. Now, it didn't only mean that; the Constitution was made in the immediate shadow of Shays's Rebellion. But it did mean that. Just as the Fugitive Slave Clause (mostly) repudiated Somerset's Case, and obliged Northern states to return escaped slaves to the South.

And just as the Three-Fifths Clause gave the Slave South a perpetual advantage in national politics. The Three-Fifths rule (or the "federal ratio," as it was called) is often misunderstood today. We, who thinks that the enslaved should have been treated as full, equal members of society, think intuitively that it should have been five-fifths. And in the context of the Direct Tax Clause, it should have been! It's not just seats in Congress that were apportioned using this ratio, it's also the federal tax burden, kind of. And in that context, the North wants the South paying as much as possible, which meant counting their slaves. But it turns out the Direct Tax Clause is of essentially no import. It's basically impossible to levy any kind of tax consistent with the apportionment rules of the Clause. So Congress just... didn't. It used other sources of revenue, like tariffs, that didn't have to be apportioned this way. The North got played.

Because, well, in the context of congressional apportionment, the "good" rule would have been to count slaves as zero fifths of a person! That would minimize their masters' representation in Congress. There was a page in America: the Book (remember that?) with a bunch of mock campaign buttons from throughout history, and one of them said something like, "I cast my five slaves' three votes for so-and-so." That's a good way to think about it. What the Three-Fifths Clause did wasn't to count slaves as less of a person; slaves weren't actually counted at all. They couldn't vote! Instead the Clause counted the slave-masters extra.

The result was a perpetual political advantage for the slave states. Not only that, it created an actual incentive for states to maximize their slave population, so as to boost their national political clout. And it wasn't enough! As I'll get into next time, it was still the case that the House of Representatives had an anti-slavery majority within about a generation of ratification. They had to carefully maintain balance in the Senate, in perpetuity, to prevent anti-slavery action at the national level.

Oh, and this is also why we have the stupid Electoral College. Remember when I said the reason no one would accept a national popular vote for president is that "the franchise was quite restrictive at the Founding"? Yeah. James Madison literally said, at the Convention, that a national popular vote was a non-starter because it would advantage the North, where suffrage was broader because there wasn't an enslaved underclass. There's just no way to do a Three-Fifths compromise in the context of a single national popular election. There's no way to cast your five slaves' three votes except through something like the Electoral College, which reflected the Compromise in that it was based on apportionment in Congress.

To forge the Union in the first place, then, they had to indulge the Slave South. This may have been necessary, but time showed within a handful of generations that it was also self-defeating. A mere four score years passed before slavery broke the Union apart. I'll tell you all about it next time.

For a variety of reasons, I don't subscribe to the belief that one must only ever refer to these persons as "enslaved," not as "slaves." The theory, as I perceive it, is that calling them "slaves" implies that they, in some sense, deserved to be enslaved? That it was their essential nature? This seems to me an entirely unwarranted inference; certainly that is not at all what I mean to convey. Also, in the context of American constitutional history I think there is good reason for using the language as it has been used historically. ↩︎

Well, it was, anyway. ↩︎